In this week’s blog post I will continue refining my election forecast model.

Shocks

In class this week, we learned about how shocks affect election outcomes. Shocks are defined as unforeseeable events such as natural disasters and pandemics.

Achen and Bartels (2017) argue that voters hold incumbent politicians accountable for natural disasters and other uncontrollable events. They call this, “blind retrospection”, to describe when voter punish the incumbent for their conditions even if the incumbent is not responsible for the unsatisfactory conditions voters feel. They draw upon the historical example of the 1916 shark attacks the decreased Woodrow Wilson’s vote share in counties where the shark attacks occurred.

However, Fowler and Hall (2018) challenge Achen and Bartels (2017). They point out that Achen and Bartels have conveniently left some counties out of their model. When those counties are included in Fowler and Hall’s replication, they reach a different conclusion than Achen and Bartels, fining no evidence that events like shark attacks significantly influence electoral outcomes.

If Achen and Bartels’ conclusion were accurate, it would indicate that voters do not vote rationally because their decision is influenced by unrelated and random events that the incumbent cannot control. Healy and Malhotra (2010) provide evidence for the contrary. In their observational study of tornado incidences and its impact on electoral outcomes, they conclude that voters reward and punish their government in accordance with how their government handles the disaster rather than the occurrence of the tornado.

Effect of Hurricanes on Incumbent Vote Share

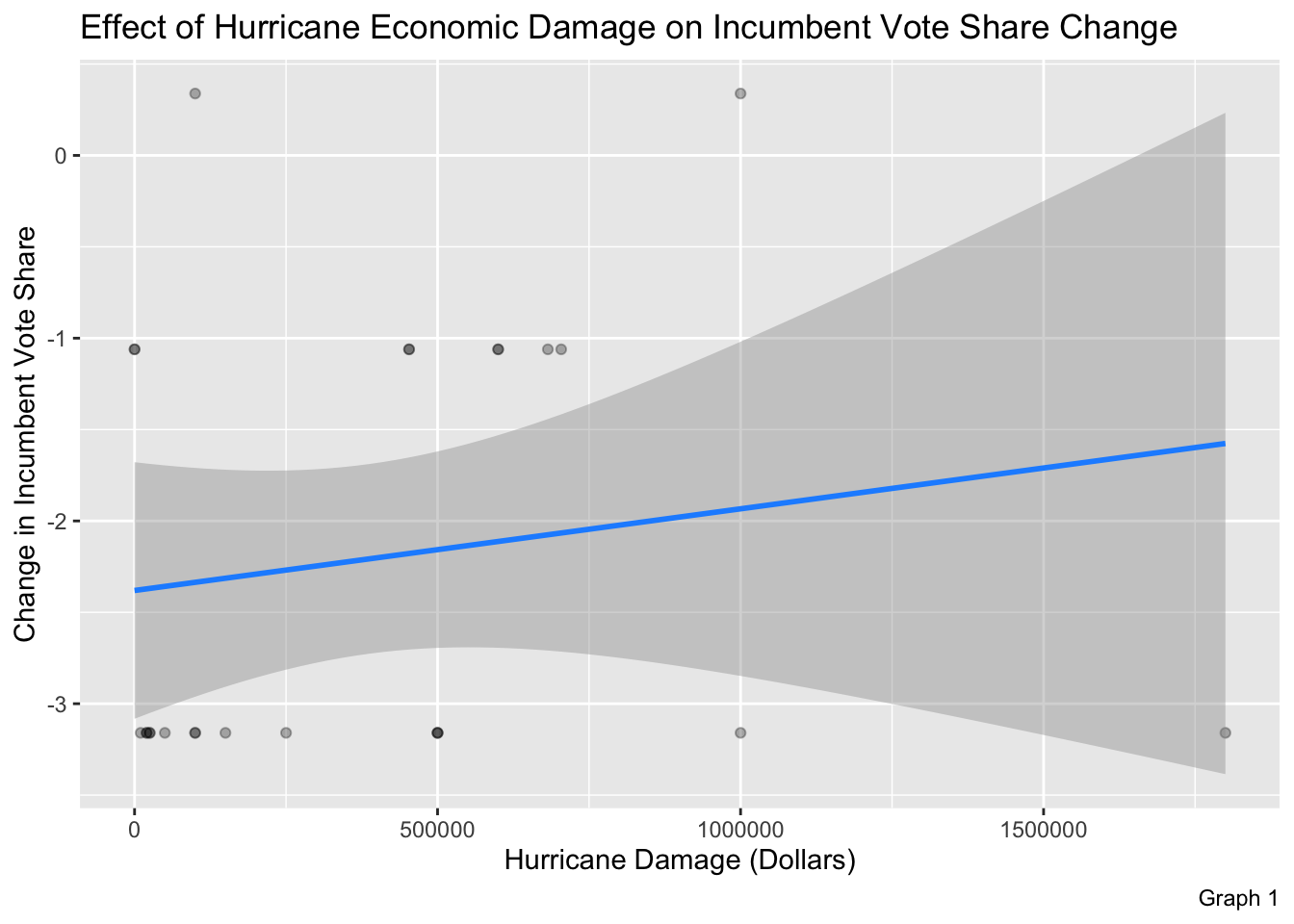

Hurricanes are an example of a shock. I ran a regression model to estimate the relationship between the economic damages a hurricane causes and how it impacts the incumbent’s vote share.

The coefficient for damage (in dollars) is 2.62e-10, meaning that for every additional dollar of hurricane damage, the incumbent’s vote share is expected to increase by a very small amount (2.62e-10 percentage points). Regardless, the p-value is nearly, 0.50, which indicates that the relationship between hurricane damage and the incumbent’s vote share change is not statistically significant. This means that voters do not punish a candidate more if the hurricane brings about more damage which suggests that there are other variables that impact the incumbent’s vote share.

In graph 1 below, it is evident there this is almost no relationship between the two variables. In fact, there is a slight positive relationship. One possible explanation is that when hurricanes cause a lot of damage, federal agencies and other states often step in to provide aid. This response may create a perception that the local government is effectively responding to the hurricane’s damage, which may result in a slight increase in support for the incumbent.

There are limitations to this data analysis, I excluded all hurricanes where there was no economic damage figure provided. On another note, I tried to use this data for my election forecast model but it would not work because I’m training my data on 2024 and this data set only goes up to 2016. Since shocks are unexpected, I can’t reliably predict the type of shock voters may experience in 2024 and its effects. Whereas, for other variables in my model I can use lagged values, I can’t for this type of data due to its unexpected and random nature.

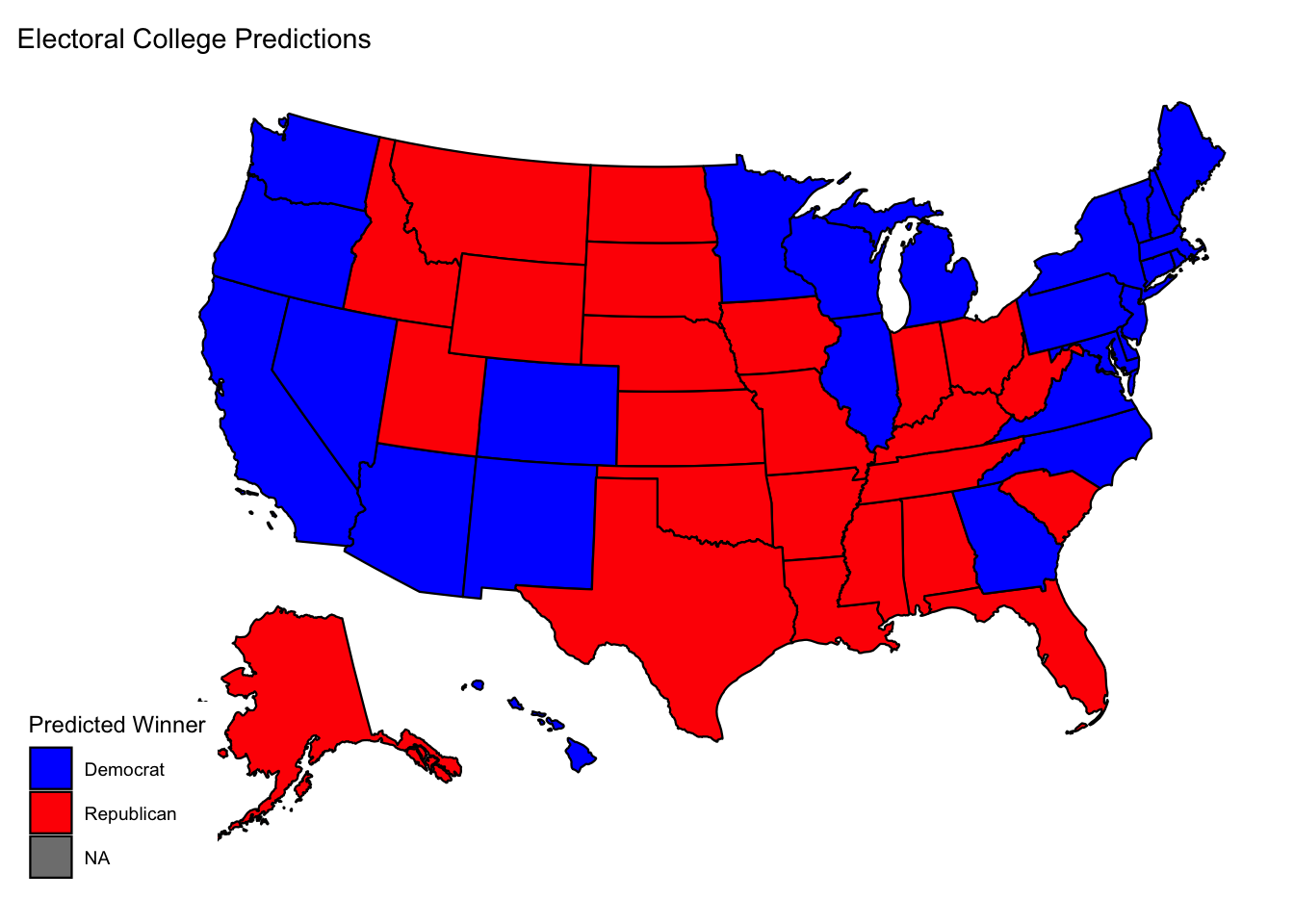

Update to my Election Forecast

In this week’s model, I decided to swap out state GDP for state Q2 GDP growth because GDP growth seems like a better measure of a state’s economy. Some states, like California, have a much larger GDP due to its population and commerce but it intuitively makes sense that comparing state GDP that varies can be standardized by comparing GDP growth (%). I removed the mean poll averages because I think it was causing multicollinearity and potentially over weighing the poll data. For the same reason, I opted to test unemployment and realized that it was causing economic indicators to have disproportionate impact on the election outcome. The variables I kept in my regression model are latest_pollav_DEM, D_pv2p_lag1, q2_gdp_growth, and disposable_income. Below is the predicted outcome. I’m surprised that by changing state GDP to state Q2 GDP growth that it has made all swing states go for Harris when in the previous blog post, six out of the seven states went for Trump. I did remove some variables this week but it shouldn’t have caused such a swing in the electoral college outcome because those variables removed were conveying similar information to the other variables in the regression model. Regardless, the table below shows the predicted two party vote share and every state is within margin of error and could go for either candidate which reflects how close this election is.

| party | total_electors |

|---|---|

| Democrat | 319 |

| Republican | 219 |

How close is this race?

| state | mean_dem | mean_rep | lower_dem | upper_dem | lower_rep | upper_rep | winner |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arizona | 50.64652 | 49.35348 | 46.95566 | 54.33738 | 45.66262 | 53.04434 | Democrat |

| Georgia | 51.13641 | 48.86359 | 47.47330 | 54.79952 | 45.20048 | 52.52670 | Democrat |

| Michigan | 51.91646 | 48.08354 | 48.22292 | 55.61000 | 44.39000 | 51.77708 | Democrat |

| Nevada | 51.45307 | 48.54693 | 47.74526 | 55.16089 | 44.83911 | 52.25474 | Democrat |

| North Carolina | 50.87932 | 49.12068 | 47.17785 | 54.58080 | 45.41920 | 52.82215 | Democrat |

| Pennsylvania | 51.41838 | 48.58162 | 47.71660 | 55.12015 | 44.87985 | 52.28340 | Democrat |

| Wisconsin | 51.64380 | 48.35620 | 47.93135 | 55.35625 | 44.64375 | 52.06865 | Democrat |

References

Achen, Christopher, and Larry Bartels. “Blind retrospection: Electoral responses to droughts, floods, and shark attacks.” Democracy for Realists, 31 Dec. 2017, pp. 116–145, https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400888740-007.

Fowler, Anthony, and Andrew B. Hall. “Do shark attacks influence presidential elections? reassessing a prominent finding on voter competence.” The Journal of Politics, vol. 80, no. 4, Oct. 2018, pp. 1423–1437, https://doi.org/10.1086/699244.

Healy, Andrew, and Neil Malhotra. “Random events, economic losses, and retrospective voting: Implications for democratic competence.” Quarterly Journal of Political Science, vol. 5, no. 2, 22 Aug. 2010, pp. 193–208, https://doi.org/10.1561/100.00009057.