In this week’s blog post I will delve into the ground game and how it impacts electoral outcomes. Additionally, I will make an update to my presidential election outcome forecast.

Will the ground game impact the presidential election outcome? The ground game is defined as on-the-ground efforts made by a campaign to engage and mobilize voters.

Available literature shows evidence that direct campaign contact and advertising has minimal persuasive effect on voters (Kalla and Broockman, 2017). As election day approaches, the persuasive effect of direct campaign contact and advertising declines (Kalla and Broockman, 2017). Does this mean that the ground game has no effect on the election outcome? Well, not exactly, Enos and Fowler argue that large-scale campaigns significantly increase voter turnout in battleground states by up to 7-8 percentage points after analyzing data from the 2012 election. Kalla and Broockman conclude that the campaign ground game does not affect who a voter will vote for because it still holds value. Enos and Fowler find that the ground game does increase voter turnout. Therefore, by strategically targeting voters in specific geographic areas they can influence who turns out.

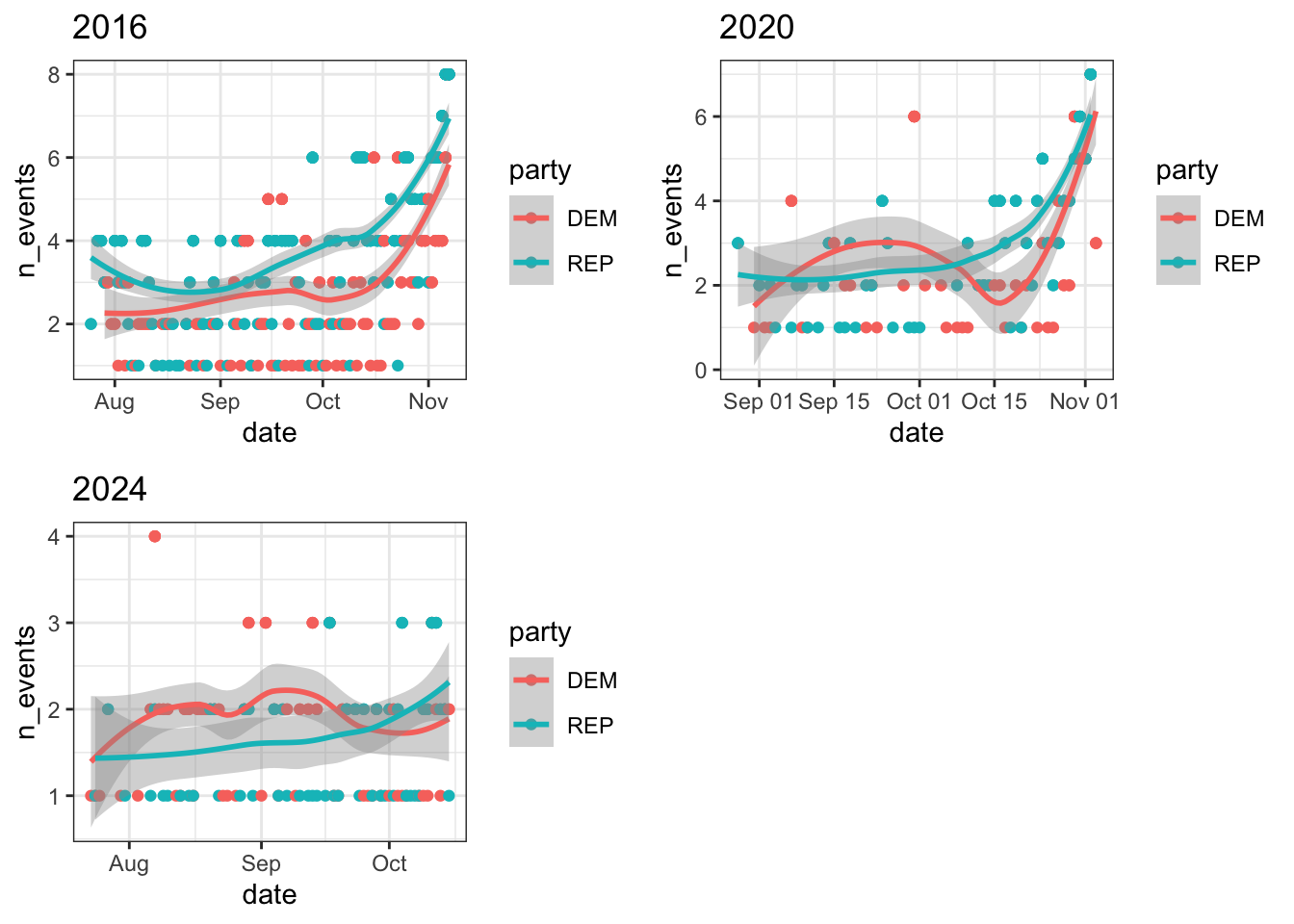

The Ground Game Visualized

In the graph above, the number of campaigns is plotted along the y-axis and the data along the x-axis for the most recent elections. As the election day approaches, the number of campaign events per week increases. The 2024 plot only has data available to the middle of October. Based on the plots from the 2016 and 2020 elections, it is expected that the number of campaign events will ramp up. It appears that the Republicans are leading in the number of campaign events.

This raises the question: does the number xof campaign events affect the voting outcomes? A linear regression model on the number of events and the difference between the Democrats and Republicans shows that the number of Democratic campaign events positively affects Democratic vote share whereas the difference in event counts shows a positive but not significant association. For Republicans, there is a small negative association with Republican vote share, and a larger difference in Republican campaign events compared to Democratic events is positively associated with Republican vote share. The linear regression model used does not mean that the number of campaign events causally explain party vote share but it does show an association.

Table: Table 1: Association Between Campaign Events and Voting Outcomes of Interest

| Term | Estimate | p-value | CI Lower | CI Upper | Party Vote Share |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 48.189 | 0.000 | 47.465 | 48.914 | D_pv2p |

| n_ev_D | 0.126 | 0.000 | 0.060 | 0.192 | D_pv2p |

| ev_diff_D_R | 0.105 | 0.121 | -0.028 | 0.237 | D_pv2p |

| (Intercept) | 51.810 | 0.000 | 51.086 | 52.535 | R_pv2p |

| n_ev_R | -0.126 | 0.000 | -0.192 | -0.060 | R_pv2p |

| ev_diff_R_D | 0.230 | 0.003 | 0.077 | 0.383 | R_pv2p |

Update to The Presidential Election Forecast

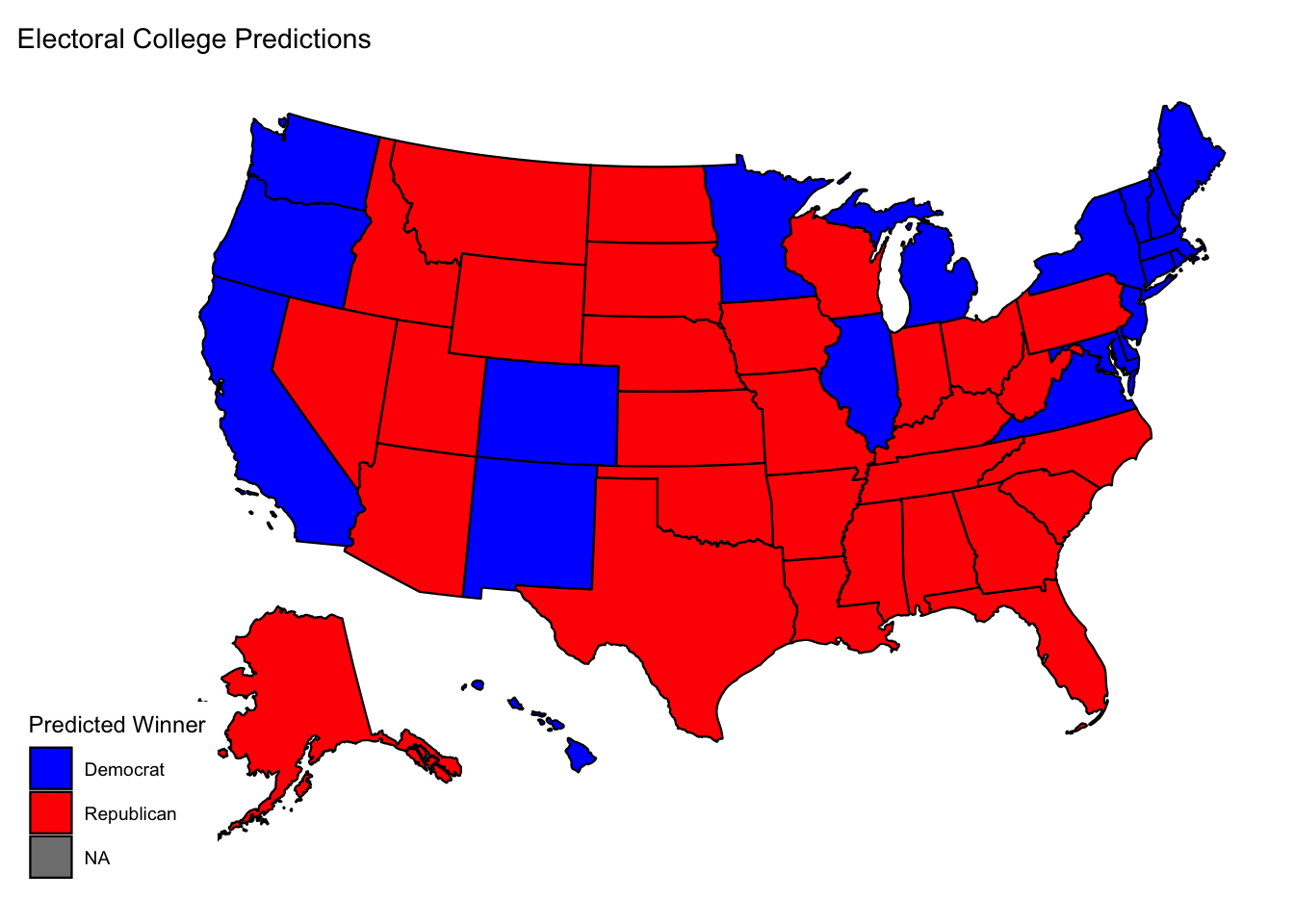

This week, I will be updating my election forecast by introducing a new variable: state gdp. State gdp is an economic indicator. I will be using quarter 2 state gdp. I am including state gdp because that is data I could find up to 2024 and similar to Alan Abramowitz’s Time for a Change Model that uses gdp growth. I added state gdp as a predictor to my model that uses linear regression and then ran 10000 simulation to create confidence intervals.

This week, Trump is still forecasted to win with an even greater electoral college margin than last week. Trump still has hold of the same battleground states as last week and has taken Wisconsin this week.

However, something important to note is that this race is very close. There are seven swing states and when I take into account the 95% confidence intervals, Harris could still win six of the seven battleground states except for North Carolina.

| party | total_electors |

|---|---|

| Democrat | 241 |

| Republican | 297 |

| state | mean_dem | mean_rep | lower_dem | upper_dem | lower_rep | upper_rep | winner |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arizona | 49.12350 | 50.87650 | 47.48170 | 50.76529 | 49.23471 | 52.51830 | Republican |

| Georgia | 49.10675 | 50.89325 | 47.48600 | 50.72750 | 49.27250 | 52.51400 | Republican |

| Michigan | 50.09219 | 49.90781 | 48.45812 | 51.72625 | 48.27375 | 51.54188 | Democrat |

| Nevada | 49.60726 | 50.39274 | 47.97487 | 51.23966 | 48.76034 | 52.02513 | Republican |

| North Carolina | 48.25019 | 51.74981 | 46.60947 | 49.89091 | 50.10909 | 53.39053 | Republican |

| Pennsylvania | 49.74566 | 50.25434 | 48.11459 | 51.37674 | 48.62326 | 51.88541 | Republican |

| Wisconsin | 49.97452 | 50.02548 | 48.35489 | 51.59415 | 48.40585 | 51.64511 | Republican |

References

Kalla, Joshua L., and David E. Broockman. “The Minimal Persuasive Effects of Campaign Contact in General Elections: Evidence from 49 Field Experiments.” American Political Science Review, vol. 112, no. 1, 2018, pp. 148–166. Cambridge University Press, doi:10.1017/S0003055417000363.

Enos, Ryan D., and Anthony Fowler. “Aggregate Effects of Large-Scale Campaigns on Voter Turnout.” Political Science Research and Methods, vol. 6, no. 4, Oct. 2018, pp. 733–751. Cambridge University Press, doi:10.1017/psrm.2016.21.